WRITING SUBTITLES

TIPS FOR NON-PROFESSIONALS

At film festivals, on online streaming sites, and even in films restored for international distribution, we see far too many inaccurate subtitles. Presumably they were created by non-professional translators, most likely volunteers.

Inaccurate subtitles – marred by careless typos, sloppy translations, inattentive transcribing, or creative rewrites – distract the viewer, distort the filmmakers’ vision, create misunderstanding – and threaten the world’s film heritage.

For example:

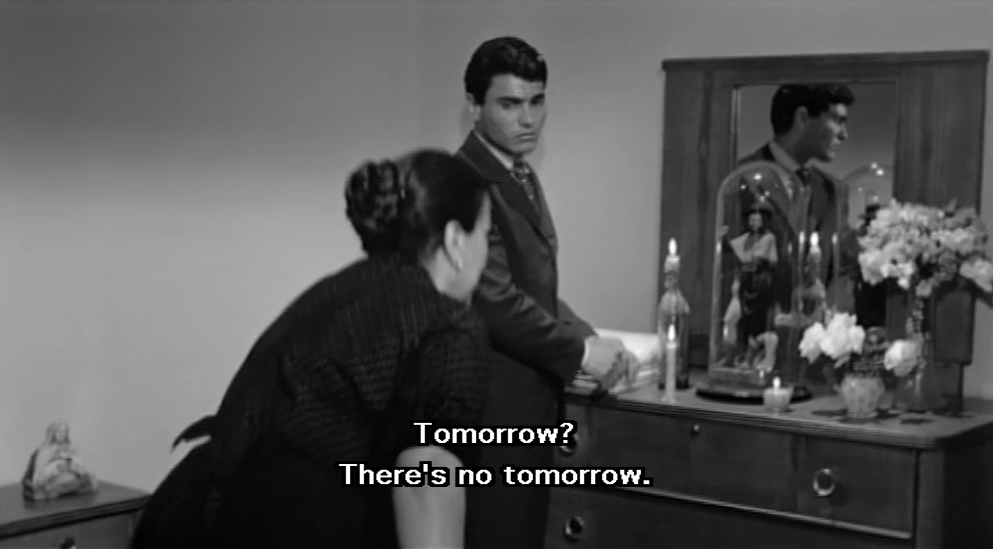

Background: Ciro tells his mother not to worry. “Tomorrow we’ll see what we can do.” His mother replies.

Line in source language (Italian): Domani? Domani sarà la stessa cosa!

Accurate translation: Tomorrow? Tomorrow will be the same thing!

Subtitle: Tomorrow? There’s no tomorrow. [Inaccurate]

Note: The translator has completely changed the meaning of this line in a renowned screenplay by master Italian screenwriters Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Massimo Franciosa, Enrico Mediola and Director Luchino Visconti.

___________

We believe that, just like novels or poetry, films deserve translations of the highest possible quality. When films are restored, the subtitles should be checked and updated. Ideally, subtitles would be created by professional translators but, given budgetary restrictions, that is not always possible in practice. Drawing on our own experience working with film subtitles, we have prepared this document to help non-professional translators do a better job.

OBLIGATIONS OF THE TRANSLATOR

As a translator, you have certain ethical obligations:

To preserve the intent of the filmmakers.

To submit the best-quality product you can.

To meet those obligations, we recommend the following.

In generating a subtitle, first make an exact transcription as you watch the film, and then create a translation that conveys the meaning of the source language as accurately as possible.

When you are finished, review your work. No matter how careful you are, you are bound to have made mistakes. In reviewing, you should re-watch the film and compare what you have written.

The final subtitles should be proofread by a native speaker of the target language.

“Girl in the Window”

Tips with Notes & Examples

TRANSCRIBING

Native speaker of source language

Exact words

Idiosyncratic elements

Proper nouns

Consistent spelling

Written material

Screenplay

TRANSLATING AND WRITING SUBTITLES

Spell-check

Context

Tone

Accurate, not literal translation

Some words: no translation

Idioms & set phrases

Cultural differences

Target language syntax

False friends

Unnecessary changes

Managing grammatical errors

Relevant written material

Background information

Conventions of target language

Logical division of words

Readabilty

PLEASE NOTE: This tipsheet is concerned with language and translation and does not include technical guidance on topics such as timing and length of subtitles; matching subtitle to speech onset; or special situations (off-screen voices, multiple speakers in a single shot, etc.).

TIPS WITH NOTES & EXAMPLES

TRANSCRIBING

In some languages — for example, Japanese — transcription is an essential first step in subtitling. In other cases, it may be a helpful tool for the subtitler. At the very least, subtitlers may want to transcribe particularly long or tricky passages so as to work with them more effectively.

The best person to transcribe dialogue would be a native speaker of the source language, who will be attuned to variant speech patterns, local idioms, accents, and cultural nuances – and plain old accuracy.

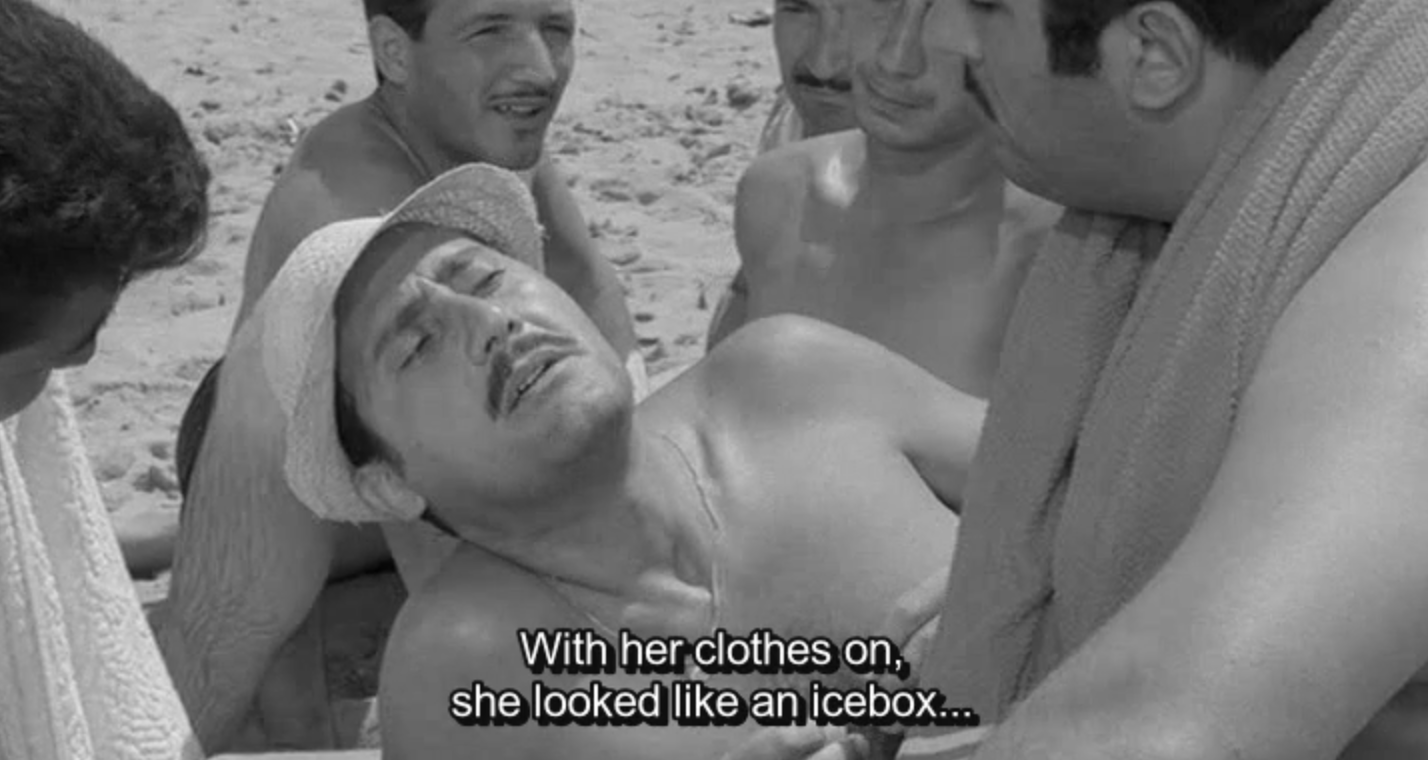

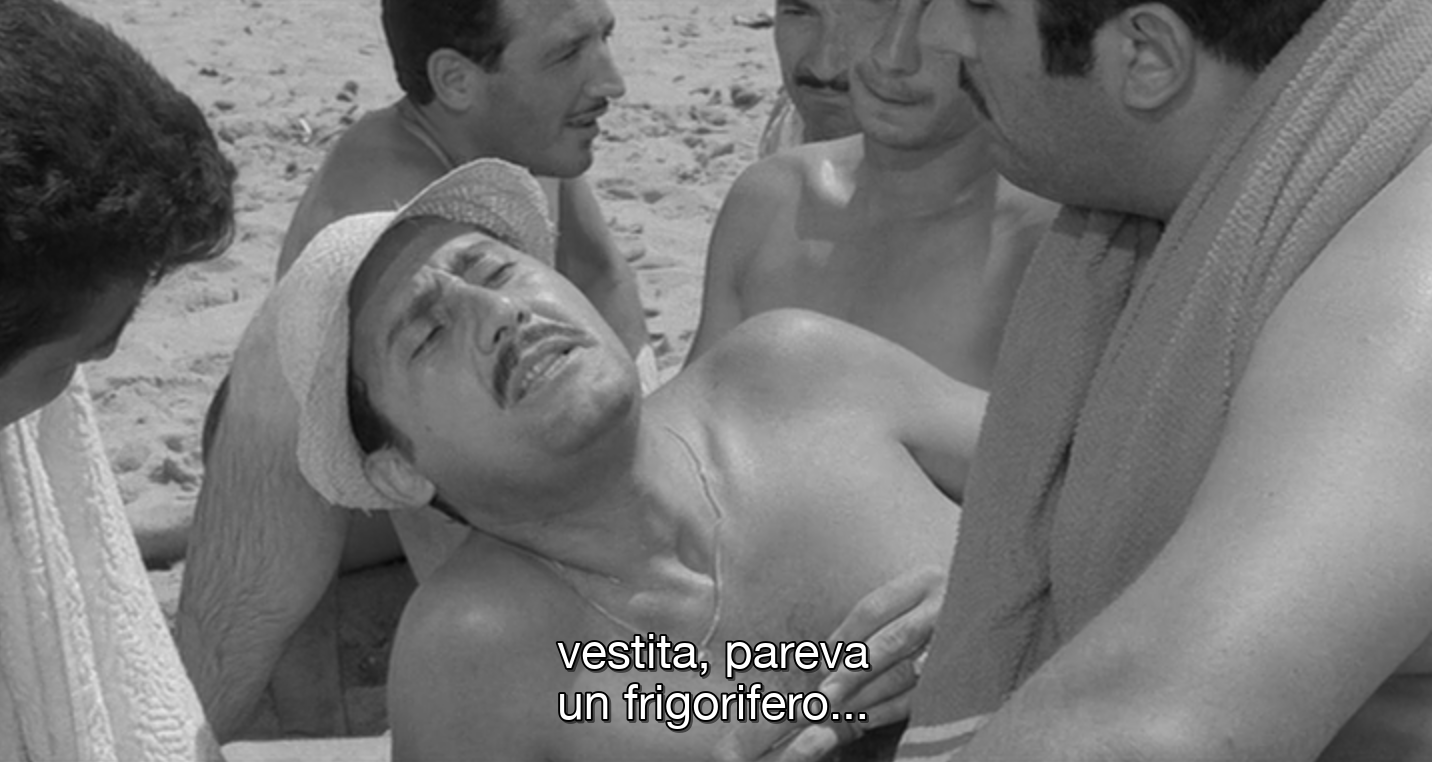

Opening lines, for context: A divorced woman. Blonde, melancholy, round.

Following line in source language (Italian): Sembrava frigida quando la vedevi vestita.

Accurate translation: She looked frigid when you saw her dressed.

English subtitle: With her clothes on, she looked like an icebox. [Inaccurate]

Italian subtitle: …vestita, pareva un frigorifero. [Inaccurate]

Note: How did this happen?

2. Write the exact words of the narrator/actor/intertitle that you hear/see. Make a change only if there is an obvious inadvertent error that is inconsistent with the film’s intent and/or with comprehensibility. Do not change the meaning, even if you think you have a better way to say it. Be sure to keep even text that won’t translate well. The translator will address that later.

Background: Far from home, on learning that his new roommates at a Dutch mine are also Italian, the Sicilian miner responds as follows.

Line in source language (Italian): Bene. Così ci faremo compagnia.

Accurate translation: Good. This way, we can keep each other company.

Subtitle: At least, we won’t get bored. [Inaccurate]

Note: A careless transcriber or translator has completely changed the meaning of the line and lost the poignancy of it.

3. Maintain idiosyncratic elements, such as extra punctuation or odd spelling.

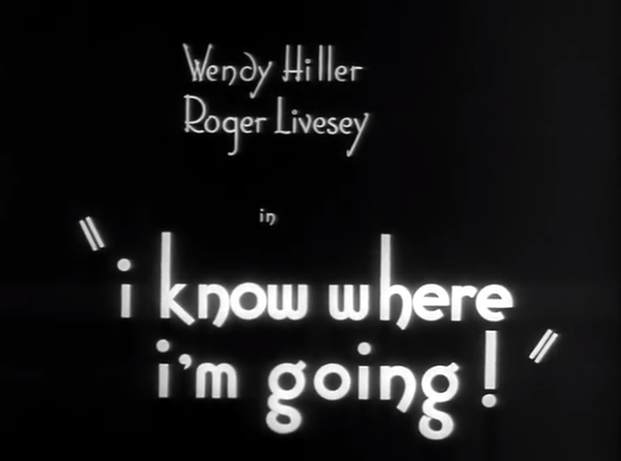

Note: The screenwriters of I Know Where I’m Going! chose to end their title with an exclamation point to emphasize the self-confidence of their independent young female protagonist. But, according to IMDb (Internet Movie Database), the only language version that maintained the original title exclamation point in translation was the Russian one: Я знаю, куда я иду!

4. Pay particular attention to proper nouns. If you encounter a name or another word you’re not sure of, research it, and then decide how to handle it in the subtitle.

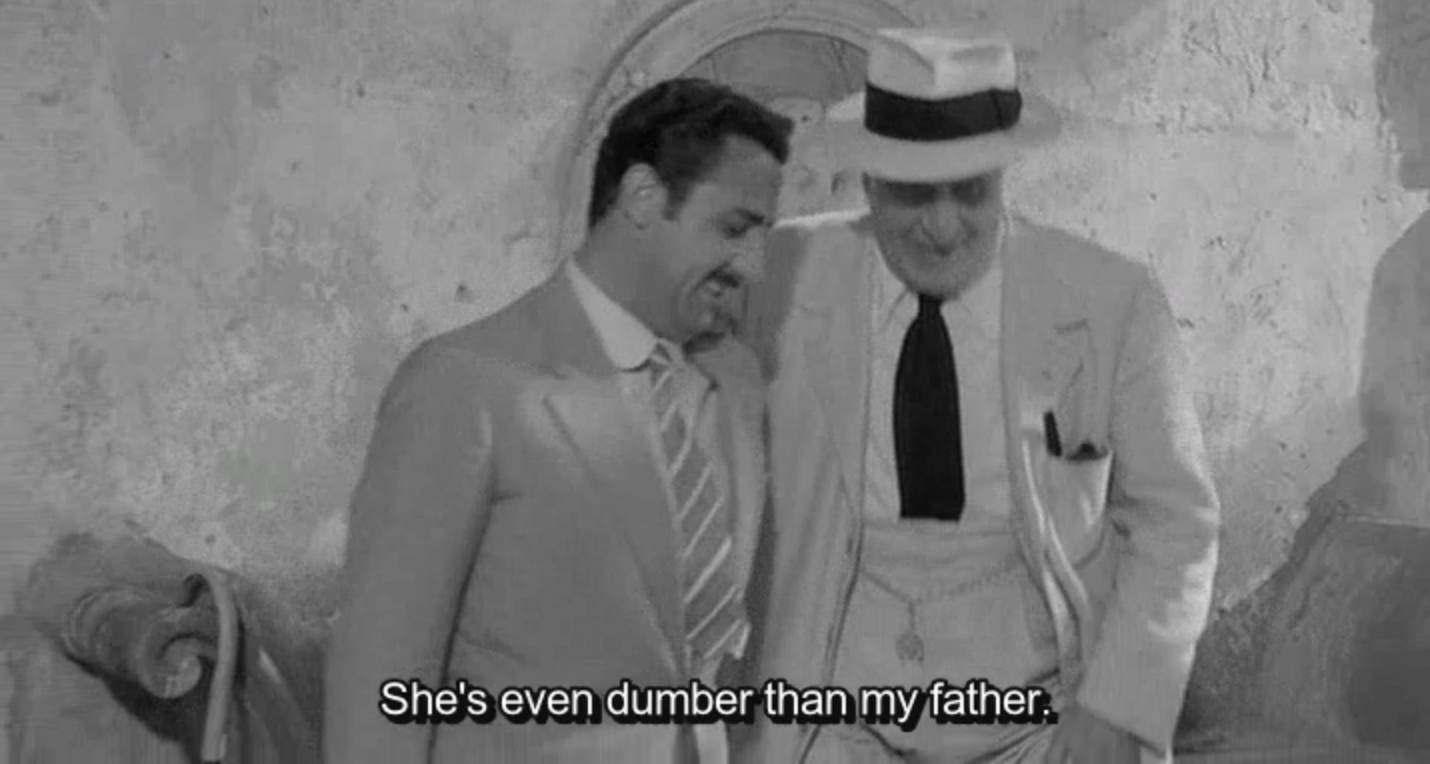

Background: The local Mafia Don speaks of Nicoletta, his housekeeper.

Line in source language (Italian): È ancora più stupida di Giufà.

Accurate translation: She’s even dumber than Giufà.

English subtitle: She’s even dumber than my father. [Inaccurate]

Italian subtitle: È più tosta di mio padre. (She’s dumber than my father.) [Inaccurate]

Note: Giufà is a folklore character based on Middle Eastern tradition, from the time of the Moors’ domination in Sicily and Southern Italy. Though often thought of as the village fool, Giufà’s stories carry moral messages. The subtitler obviously cannot include all this background information, but the subtitle as presented doesn’t make any sense; it’s misleading and distracting for viewers – including hearing impaired and other Italian speakers watching with the Italian subs. The best bet might be to leave the line out.

5. If you are unable to identify a word or to find its correct spelling, decide how you will write it and use the same spelling each time that it appears. Make a notation, including the timecode.

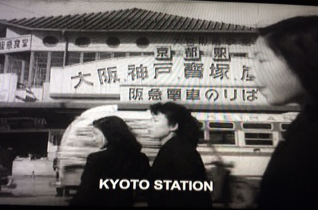

6. Be sure to transcribe any written material on the screen that is relevant to the viewer’s understanding of the movie, including signage, correspondence, and text messages.

Subtitle: Kyoto Station

Note: In this scene, the viewer needs to know that the building is the train station. That information is provided appropriately in the subtitle.

7. The screenplay and/or shooting script can be useful. However, there may be errors even there. Use caution.

Girl in the Window (screenplay)

Actual spoken line (Dutch): Vieze vuile kolerehoer.

Literal translation: Filthy choleric whore.

Incorrectly transcribed line in the screenplay: Viese kleren. (Damned clothes.)

Its translation in the screenplay to the target language (Italian): Vestiti maledetti. (Damn clothes.)

Note: In this case, ‘“kolerehoer” apparently sounded like “kleren” to the transcriber.

TRANSLATING AND WRITING SUBTITLES

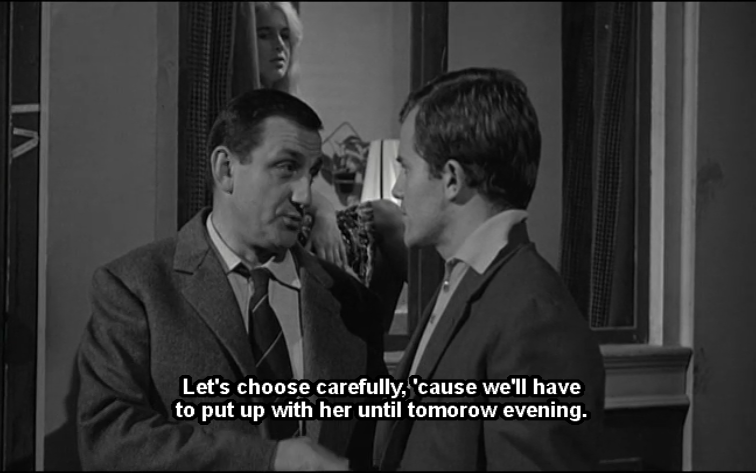

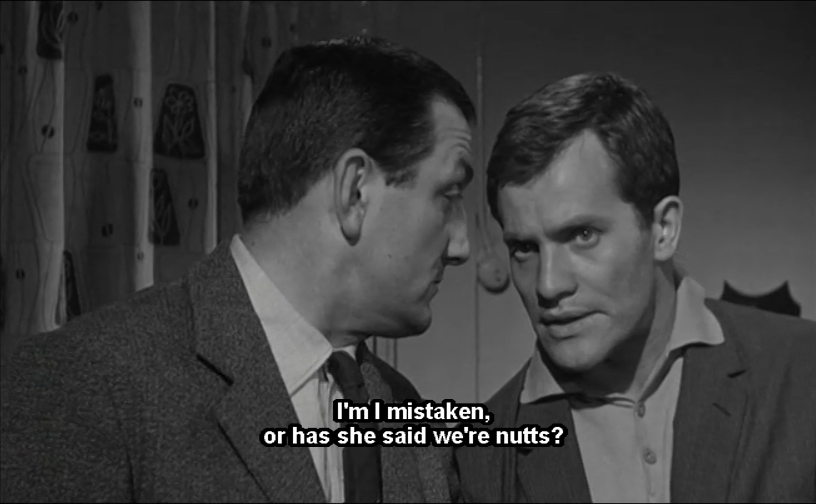

1. Although you cannot totally rely on it – see our Proofreading note below – have spell-check turned on as you work in the target language to help you catch typographical errors like these:

Typo: half an jour Correct: half an hour

Typo: tomorow Correct: tomorrow

Typo: extatic Correct: ecstatic

Typo: nutts Correct: nuts

2. If there are two ways to translate something, be attentive and make sure of the context as you watch the film.

Line in source language (Italian): Ci riposiamo lì...

Accurate translation: We’ll just lie there…

Subtitle: We’re just laying here… [Inaccurate]

3. Your translation should convey the tone (e.g., formal or conversational) as well as the meaning of the original into the target language as closely as possible.

Line in source language (Italian): "Volete qualcosa da mangiare?"

Accurate translation: “Do you want something to eat?”

Subtitle: “Wanna grab a bite?” [Inaccurate]

Note: The proprietor asks his new guests politely and in standard Italian if they would like to eat. There was no implication of rushing, as implied by the phrase “grab a bite.” This translation distorts the viewer’s perception of the proprietor and the situation.

4. A simple word-for-word – literal – translation is not adequate, and may even be incorrect.

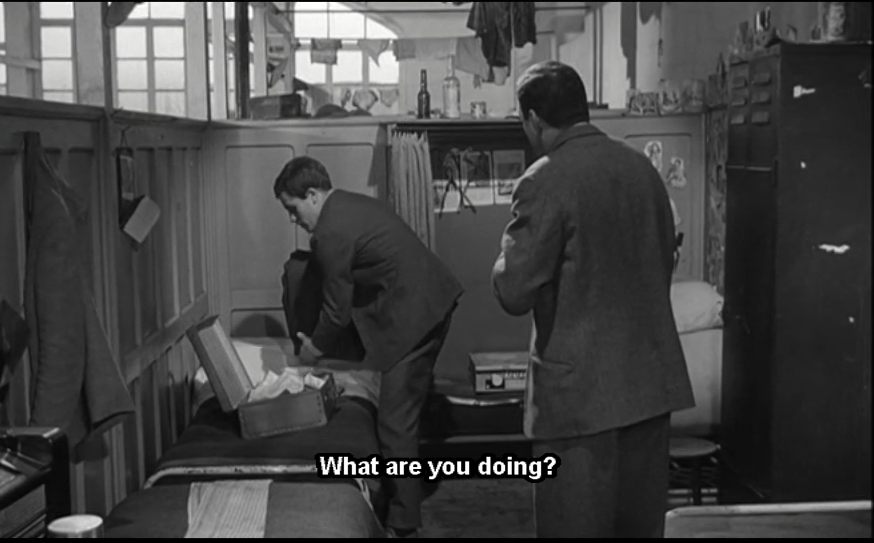

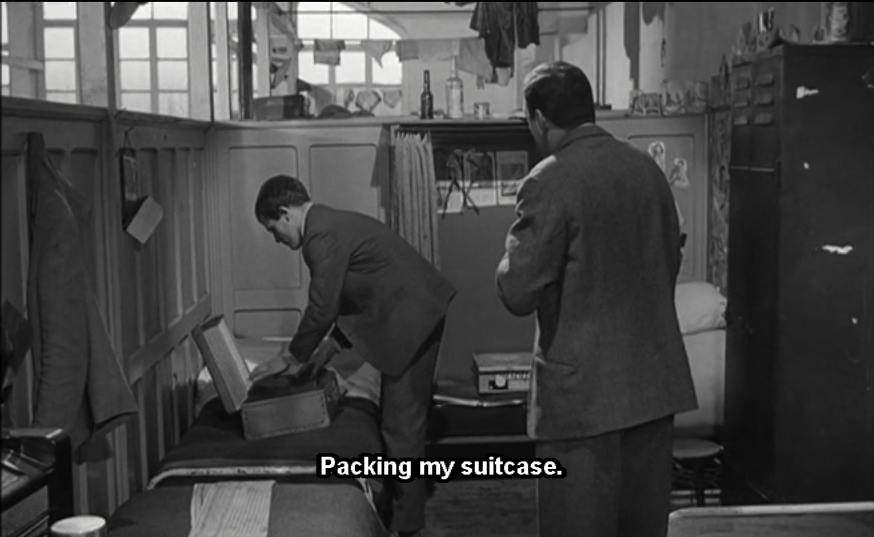

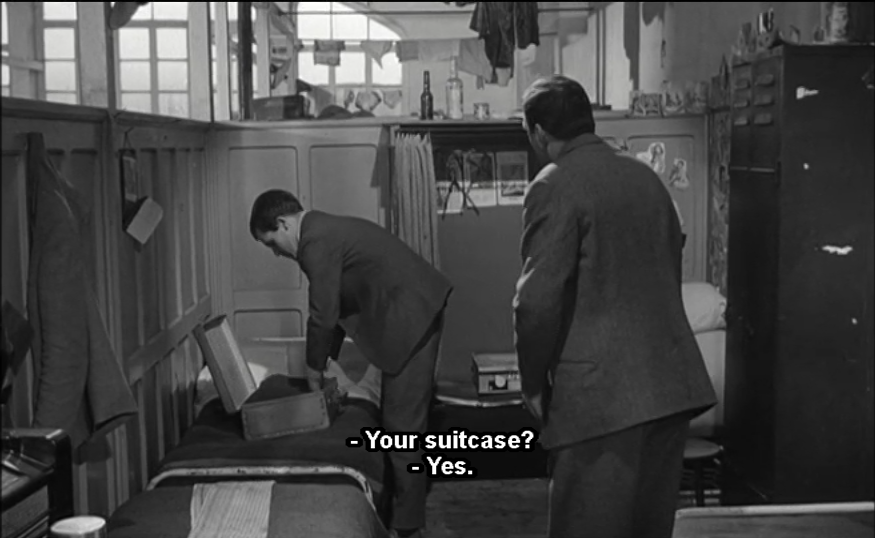

Lines in source language (Italian):

Federico: Cosa fai?

Vincenzo: La valigia.

Federico: La valigia?

Subtitles:

What are you doing? [Accurate]

Packing my suitcase. [Accurate] Note: “Packing” alone would also have been accurate.

Your suitcase? [Inaccurate]

Accurate translation: Packing?

__________

In the following case, the translator has appropriately adapted the language to maintain the rhythm of the line.

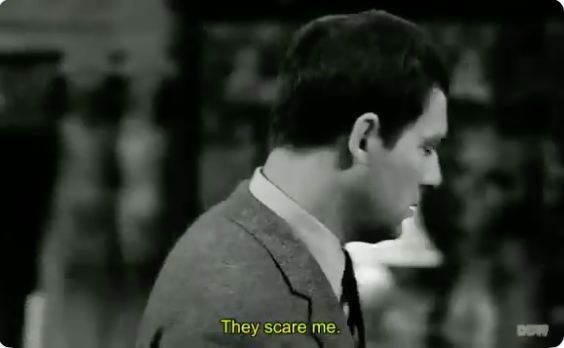

Line in source language (French): Elles me font peur. Peur! Peur!

Accurate subtitle: They scare me. Scare me!

Literal translation: They scare me. Fear! Fear!

The translator hasn’t changed the meaning of the line but has chosen a version that sits easily on the ear of the English speaker. Perhaps you think it should be translated more literally. But think of it this way: a hyper-literal translation of “Elles me font peur” would be “They make me fear.” Any subtitle must have a vernacular ease for the viewer.

5. Be aware of words and phrases that should be carried unchanged into the target language.

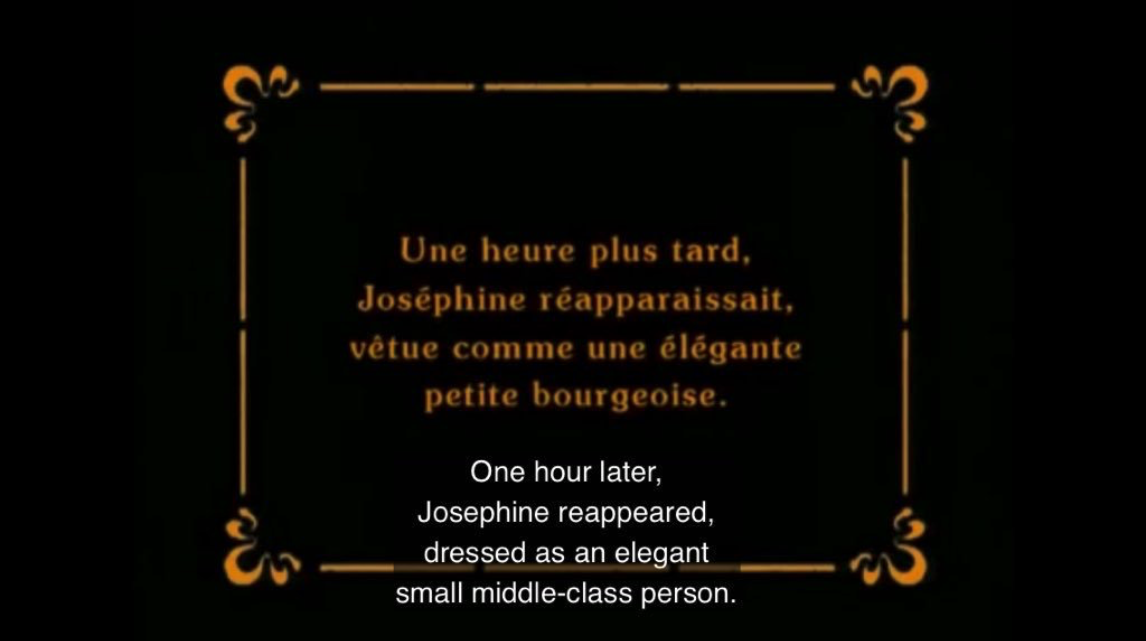

Line in source language (French): … une élégante petite bourgeoise.

Accurate translation: … an elegant petite bourgeoise. [This phrase should not be translated]

Subtitle: … an elegant small middle-class person. [Inaccurate]

__________

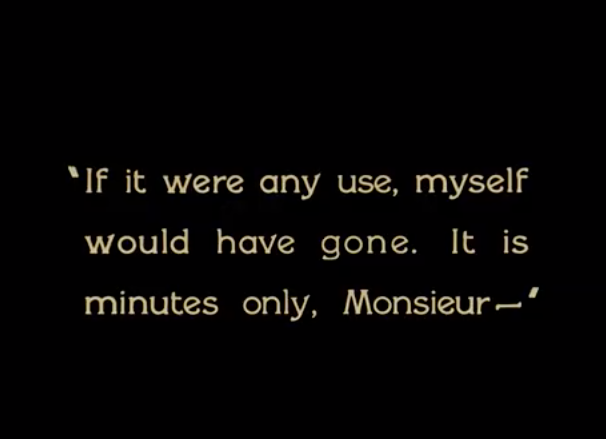

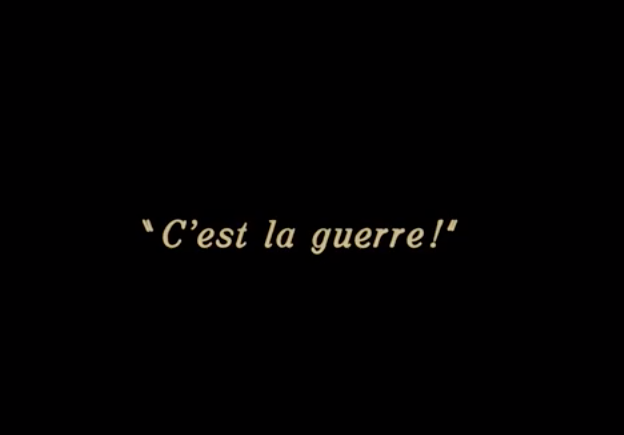

Note that in the following intertitles, French words which are commonly understood by English speakers have appropriately not been translated, and the first quote maintains a foreign syntax, even though it has been translated into English. This helps maintain a sense of time, place, and character.

Intertitle: … If it were any use, myself would have gone. It is minutes only, Monsieur – [Accurate]

Intertitle: C’est la guerre! [Accurate]

6. Look out for words, idioms, and set phrases that cannot be literally translated. Do your best job of conveying the idea.

Background: A group of migrants from Sicily arrives in the North and are greeted with derision by workers there.

Line in source language (Lombardy dialect >> Italian): Arrivano i terroni!

Subtitle: There they are, the “terroni” (dirty southerners).

Better option: Here come the dirty southerners!

Note: A subtitle is not the place for a language lesson; it is distracting. In this case, it is also unnecessary, since the idea of the word “terroni” can be translated.

By the same token, use an idiomatic phrase in the target language if it is the most accurate translation.

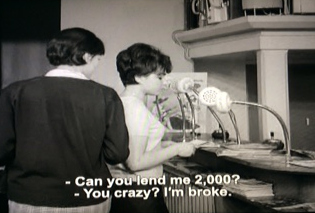

Background: Nana asks to borrow money from her co-worker.

Line in source language (French): Je n'ai rien.

Literal translation: I don’t have anything.

Subtitle: I’m broke. [Accurate]

7. Be aware of cultural differences.

Line in source language (Dutch): Vieze vuile kolerehoer!

Literal translation: Filthy choleric whore!

French subtitle: Sale pute! Sale pute de mere! (Dirty whore! Dirty fucking whore!) [Accurate]

English subtitle: None.

Note: In this case, the translator has appropriately left out the word “choleric” and chosen a culturally accurate translation.

Also note: This scene was not subtitled at all in the English version. In English, the target language, diseases are not used as intensifiers in curses. You must find a way to translate essential dialogue and other relevant language.

8. Be sure to adhere to the syntax of the target language. If there is a choice between different words or sentence structures, select the one that corresponds most closely to the source language. This is less distracting for bilingual viewers.

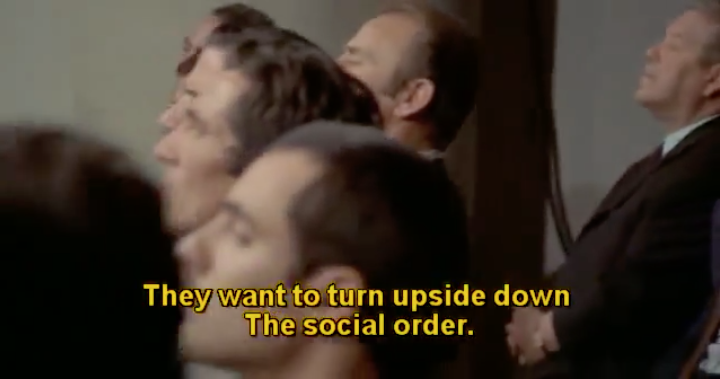

Line in source language (Italian): “E cioè al rovesciamento dell’attuale ordine sociale”.

English subtitle: They want to turn upside down

The social order.

Accurate translation: They want to turn the social order upside down.

Note: The translator has carried over the structure of the sentence from the source language and produced a subtitle that is baffling and doesn’t clearly reflect the meaning of the original. It’s even more difficult to understand this caption because the translator has chosen to capitalize the first word of the second line (“The”).

9. Be alert for false friends: that is, words that look similar in the two languages, but actually have very different meanings.

Italian to English: Wrong: educato > educated Right: educato > polite

English to Italian: Wrong: educated > educato Right: educated > istruito

10. Do not change the original text, except for clarity or for reasons of space. You may think you could write it better, but that is not your role: your role is to serve the script.

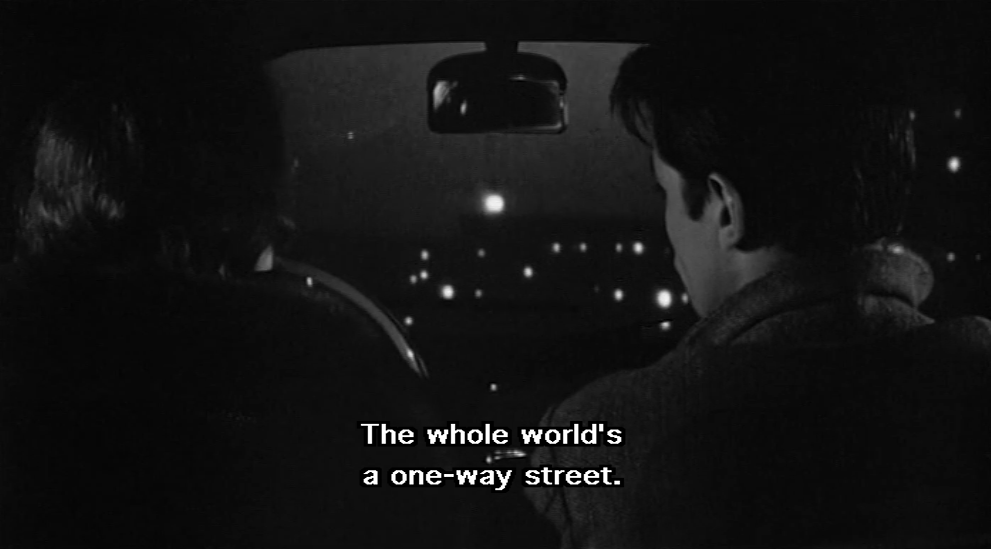

Line in source language (Italian): Dimmi un po’ tu cosa c’è che non è vietato al giorno d’oggi.

Accurate translation: Tell me something that isn’t prohibited these days.

Subtitle: The whole world’s a one-way street. [Inaccurate]

Note: This unnecessary change alters the meaning of the line. The screenwriters were expert practitioners of their craft. Don’t imagine that you know better.

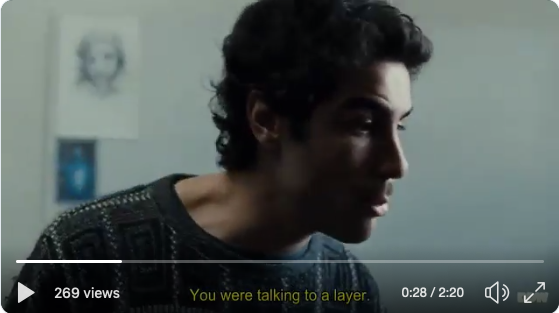

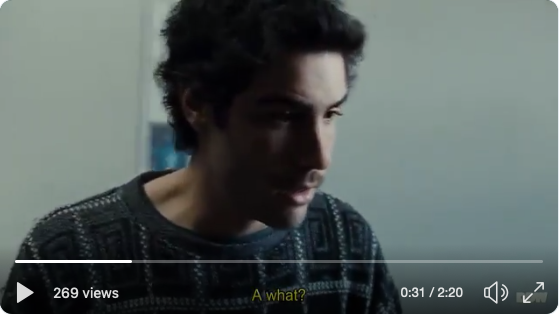

11. In cases where the script contains grammatical errors, respect the filmmakers’ intent. For example, if the source language is incorrect because it reflects the diction of the person speaking, do not correct the grammar. In resolving any translation problem, the same rule applies: respect the filmmakers’ intent.

Background: Malik has taught himself Corsican and demonstrates his knowledge in talking with César. The following subtitles appropriately maintain an error in his speech.

Subtitles:

Malik: You were talking to a layer.

César: A what?

Malik: A lawyer?

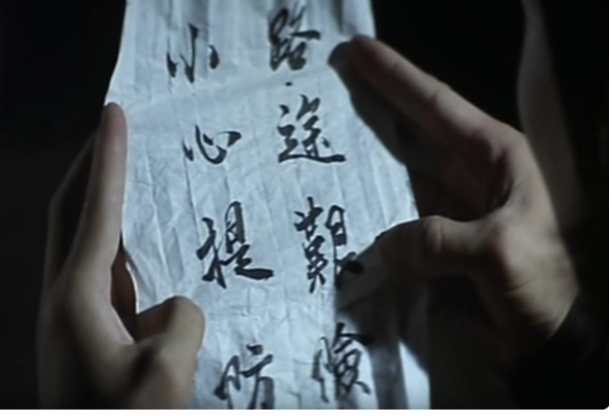

12. In case the transcriber has missed it, include relevant material that appears on the screen, including signage, correspondence and text messages that are intended to be read and understood by viewers.

Translation: (from Chinese) The journey is difficult & dangerous. Be careful.

Subtitle: None.

13. Your translation will be better if you have background information about the film and the filmmakers’ intent.

Line in source language (Italian): Sembra fatta a mano, no?

Accurate translation: She seems hand-made, doesn’t she?

Subtitle: It’s tailor-made. [Inaccurate]

Note: Let’s leave aside the error in referring to a person as “it” rather than “she.” The translation is not accurate. Rodolfo Sonego, who wrote the story and outline on which this script is based, references “these porcelain dolls all made up under the lights of the shop windows.”* What the line means is that the women on display in Amsterdam’s red-light district were like hand-made dolls, not that they were “tailor-made” for the desires of men, an entirely different idea. This background information would have been useful for the translator.

* Il cervello di Alberto Sordi. Rodolfo Sonego e il suo cinema, edited by Tatti Sanguineti, Adelphi, Milan, 2015.

14. Follow the conventions of the target language. For example, in English, all content words of titles are capitalized: Rocco and His Brothers.

15. In dividing the words within one subtitle and between successive subtitles, bear in mind the syntax of the target language. Try to create subtitles of more or less equal length, while keeping logical word groups together for ease of reading. Never leave a widow, which is a one-word subtitle concluding a long prior subtitle. For a more detailed explanation and examples of line breaks at natural points, see the BBC Subtitle Guidelines, Section 3.4.

16. Readability is key. Following the guidelines above – and using common sense for any tricky situations that arise – should provide the viewer with a frictionless experience, in which reading the subtitles costs no effort at all. Remember also that people who are hearing impaired and many speakers of English as a second language rely upon English subtitles to watch films in languages with which they are not familiar. Errors and awkward constructions are even more distracting for them.

Another aspect of readability is that subtitles must be brief, so that the eye can quickly take them in. This means that you will not always be able to include everything. Craft the content as best you can to convey the filmmaker’s intent. Identify the essential information, and include that.

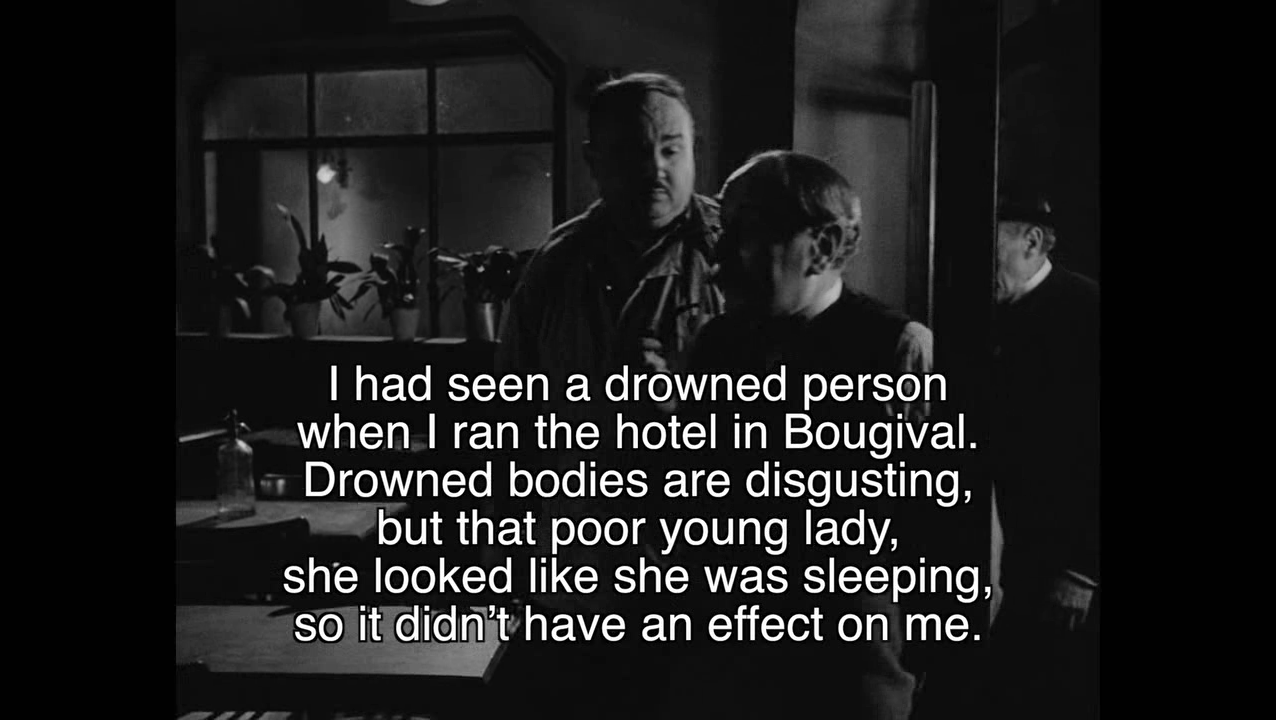

Line in translation (from French): I had seen a drowned person when I ran the hotel in Bougival. Drowned bodies are disgusting, but that poor young lady, she looked like she was sleeping, so it didn’t have an effect on me.

Subtitle: A drowned person looks awful, but this poor lady seemed asleep. [Accurate]

In this example, taken from the documentary short The Art of Subtitling, you see on the left a subtitle that includes every word spoken by the character. On the right is the actual subtitle from the 1948 version of the film.

PROOFREADING

Once completed, the subtitles should be proofread. The proofreader should be a native speaker of the target language who understands its nuances, and who should watch the film while making the necessary corrections.

That would avoid errors such as the following, which we saw in an Italian documentary: in referring to the hiring process for a group of secretaries, the subtitle used the verb “procure,” which in English generally means the recruiting of prostitutes. Even a person fluent in English as a second language might not have been aware of that usage.

The following subtitle was probably written by a native speaker of the source language. A proofreader in the target language would have noticed the problem immediately.

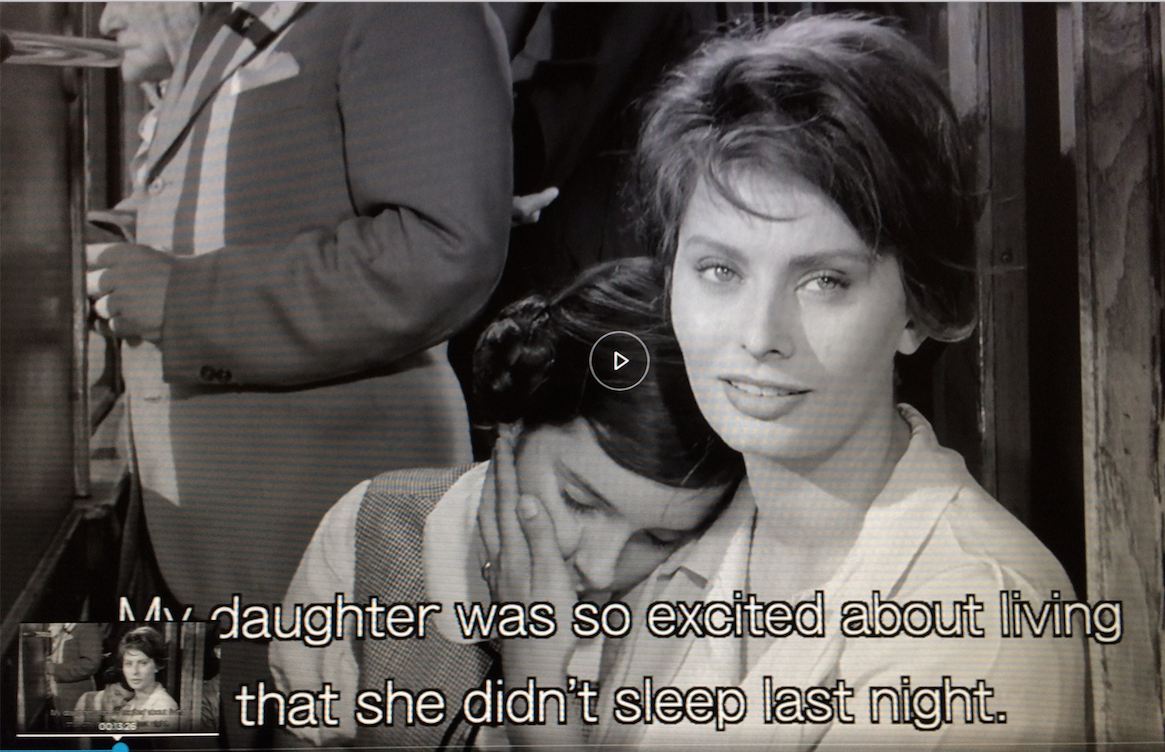

Line in source language (Italian): Per la smania di partire non ha potuto dormire tutto la notte.

Accurate translation: With the excitement about leaving she couldn’t sleep the whole night. (emphasis added)

Subtitle: My daughter was so excited about living that she didn’t sleep last night. (emphasis added) [Inaccurate]

As a translator, whether you are creating subtitles for a restored masterpiece, for a festival film whose subtitles may be seen only once, or for a pirate site where no one knows who you are, you have an important responsibility: to make the films as accessible as possible to the viewing public; to reflect the original intent of the filmmakers; and – particularly in the case of masterpieces – to honor the artistry of the screenwriters.

Dear Reader,

This document is a work in progress. Please send us your suggestions, as well as examples of exemplary or egregious subtitles that you encounter, for possible inclusion – especially examples of points that have not been illustrated here. Keep in mind: our purpose is to educate and improve the landscape of subtitles. Please send the examples as screenshots, which must include the subtitle in the image. Let us know the film’s title, director and year of release. Don’t tell us what version it is! We don’t want to know!

Submissions and comments about this post can be sent to us at: info@liconoscevobene.net

MANY THANKS to the following people, some of whom are professional translators, who contributed ideas:

Victor Acosta

And special thanks to my editor, Alberto Maio, for his skill, patience and insight, that help bring us beyond the subtitles in our storytelling.

FILM CREDITS

(All titles are in English first, in alphabetical order; screenwriter is included where relevant for our example.)

The Art of Subtitling – Bruce Goldstein, 2018

Fantômas – Louis Feuillade, 1913–14

The Fire Within / Le feu follet – Louis Malle, 1963

The Garden of Women / 女の園 – Keisuke Kinoshita, 1954

Girl in the Window / La ragazza in vetrina – Luciano Emmer, 1961. Screenplay: Luciano Emmer, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Emanuele Cassuto, Luciano Martino, Vincenzo Marinucci, Rodolfo Sonego

Hangmen Also Die! – Fritz Lang, 1943

I Know Where I'm Going! – Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger (directors and screenwriters), 1945

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion / Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto – Elio Petri, 1970

The Invincible Armor – See-Yuen Ng, 1977

Mafioso – Alberto Lattuada,1962

My Life to Live / Vivre sa vie : film en douze tableaux – Jean-Luc Godard, 1962

Panique – Julien Duvivier, 1946

Path of Hope / Il cammino della speranza – Pietro Germi, 1950

A Prophet / Un prophète – Jacques Audiard, 2009

Rocco and His Brothers / Rocco e i suoi fratelli – Luchino Visconti, 1960. Screenplay: Luchino Visconti, Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Massimo Franciosa, and Enrico Mediola

Two Women / La ciociara – Vittorio De Sica, 1960. screenplay: Cesare Zavattini

Wings – William Wellman, 1927