Regia / Director: Mario Monicelli, 1963

Vediamo Raoul che corre lungo una strada davanti a cumuli di neve ghiacciata. Si ferma davanti a una casa e grida: "Omero!"

We see Raoul running down a street past frozen mounds of snow. He stops at a house and yells, “Omero!”

Poi saltiamo al portico davanti alla casa di Niobe, dove Omero chiama: "Professore!" È appollaiato sulla parte anteriore di una bicicletta; lo zio di Adele lo ha portato lì. È la stessa bicicletta che lo zio usa quando affila i coltelli.

Omero scende e grida di nuovo: "Professore!"

Then we jump to the portico in front of Niobe’s place, where Omero calls out, “Professor!” He’s perched on the front of a bicycle; Adele’s uncle has carried him there. It’s the same bike that the uncle uses when he’s sharpening knives.

Omero gets off and yells again, “Professor!”

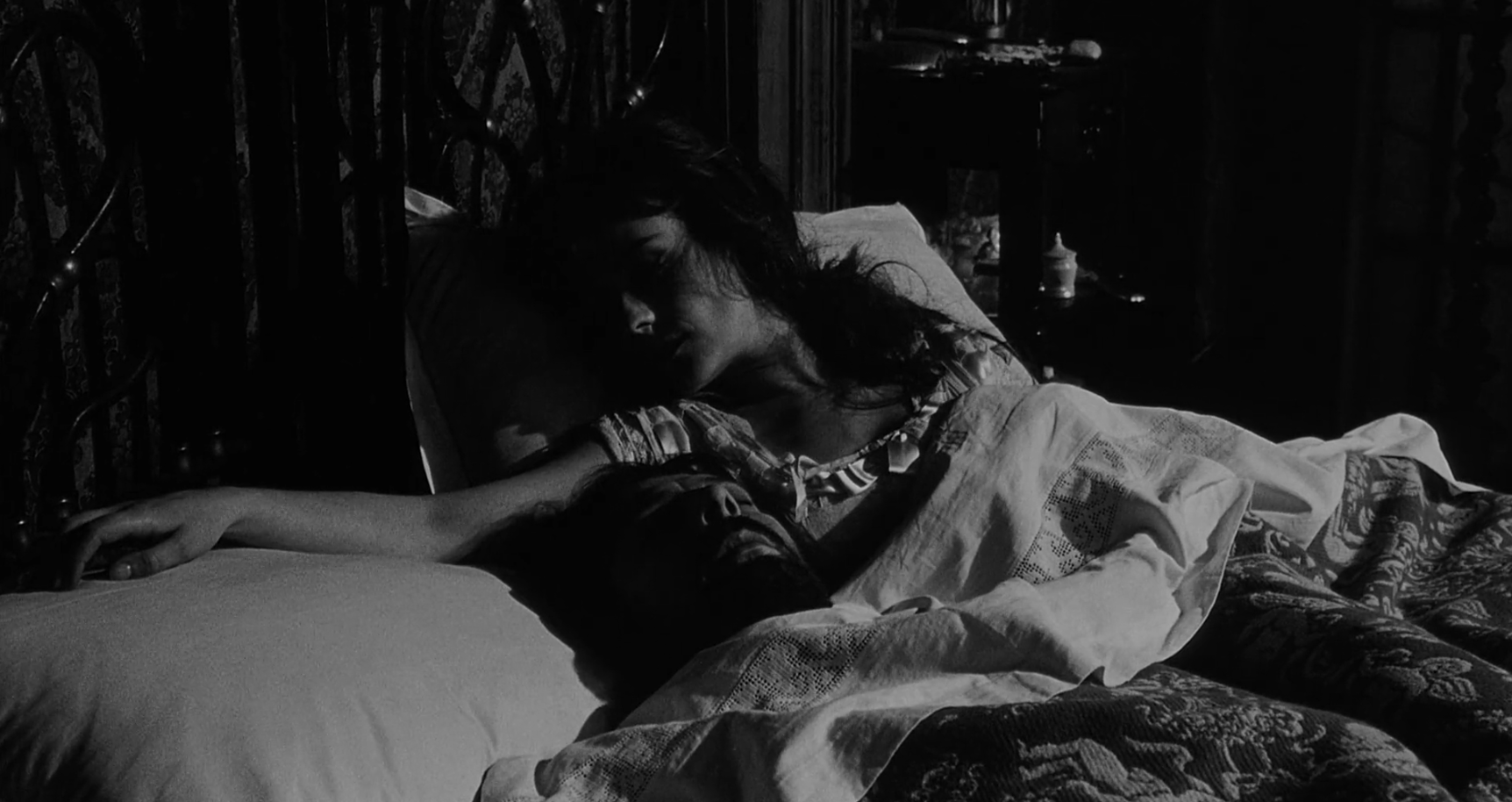

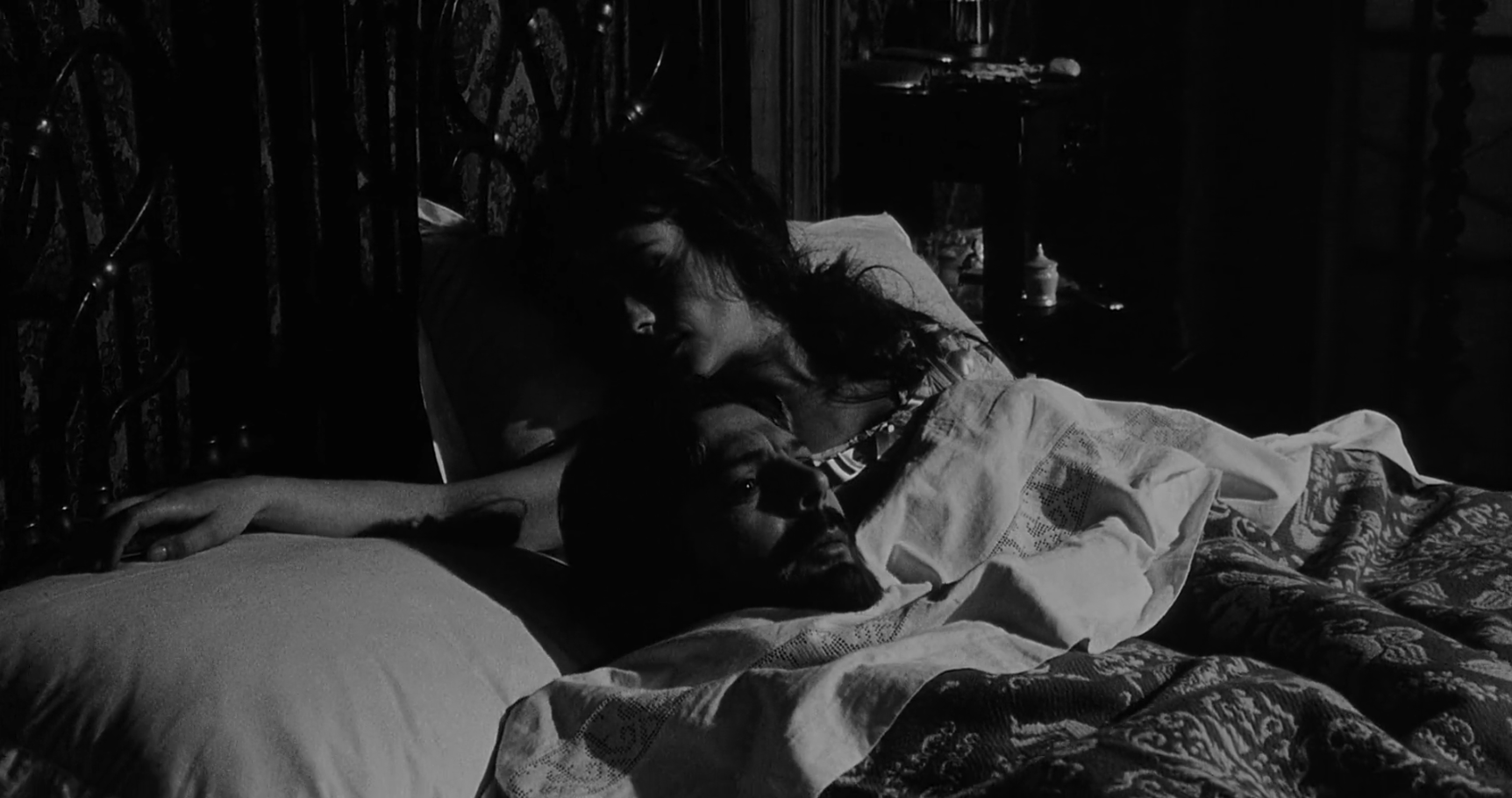

Niobe e il professore dormono profondamente. Ma lui si sveglia di soprassalto quando un sasso colpisce il lato dell'edificio. "Professore! Sono Omero!"

Niobe and the Professor are sound asleep. But he wakes with a start when a stone hits the side of the building. “Professor! It’s Omero!”

In mutande invernali, il professore va al balcone. "Cosa vuoi?"

"Mi manda Raoul. Vuole che venga subito! Vogliono tornare in fabbrica!"

Dall'alto, vediamo Omero e lo zio che guardano in alto, mentre uomini con cappelli e cappotti pesanti passano senza notare.

In his long underwear, the Professor goes to the balcony. “What do you want?”

“Raoul sent me. He wants you to come right away! They want to go back to work!”

From above, we see Omero and the uncle gazing up, while men in hats and heavy coats pass by without noticing.

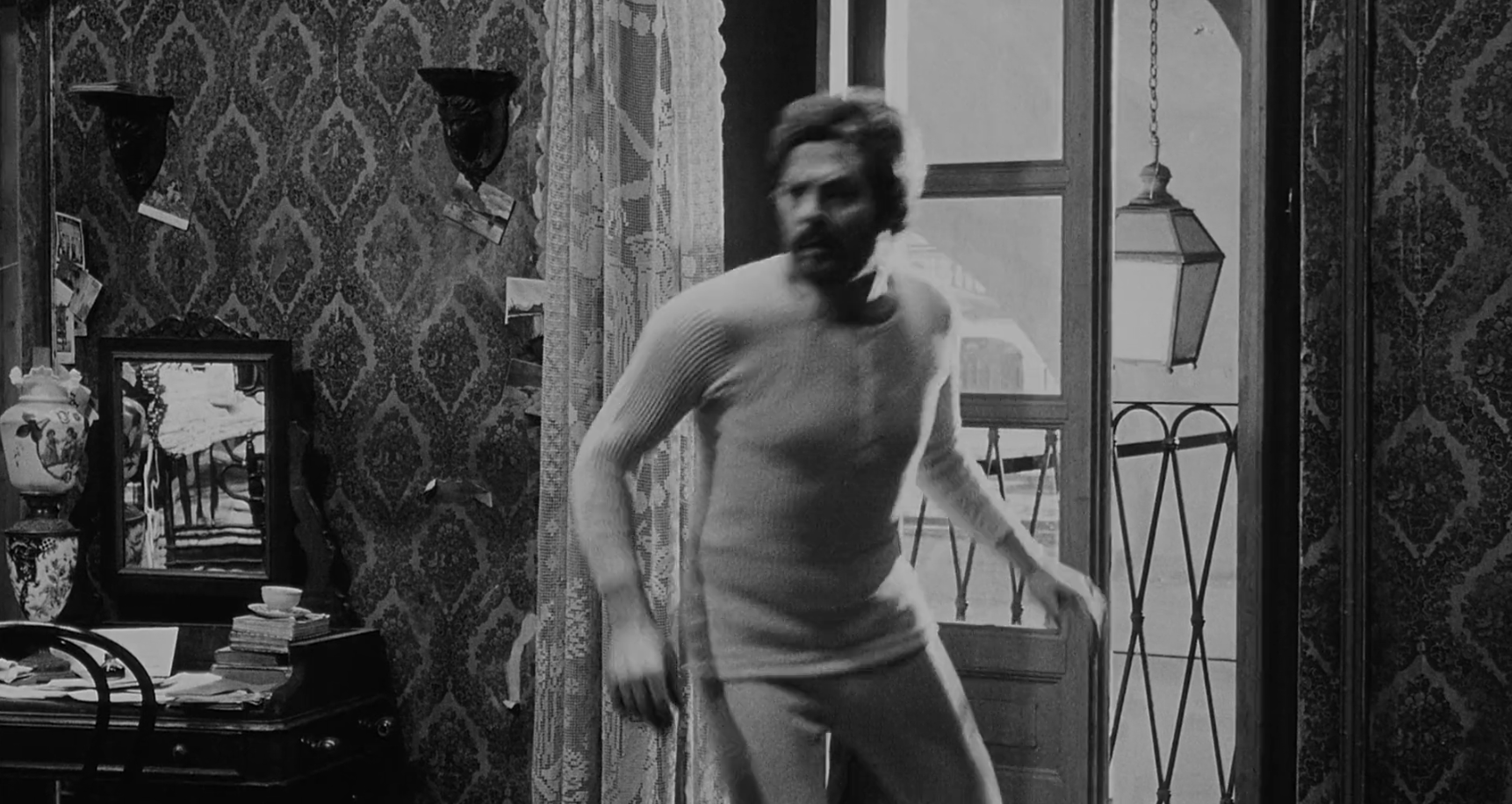

Il professore si precipita di nuovo dentro. “Maledizione!”

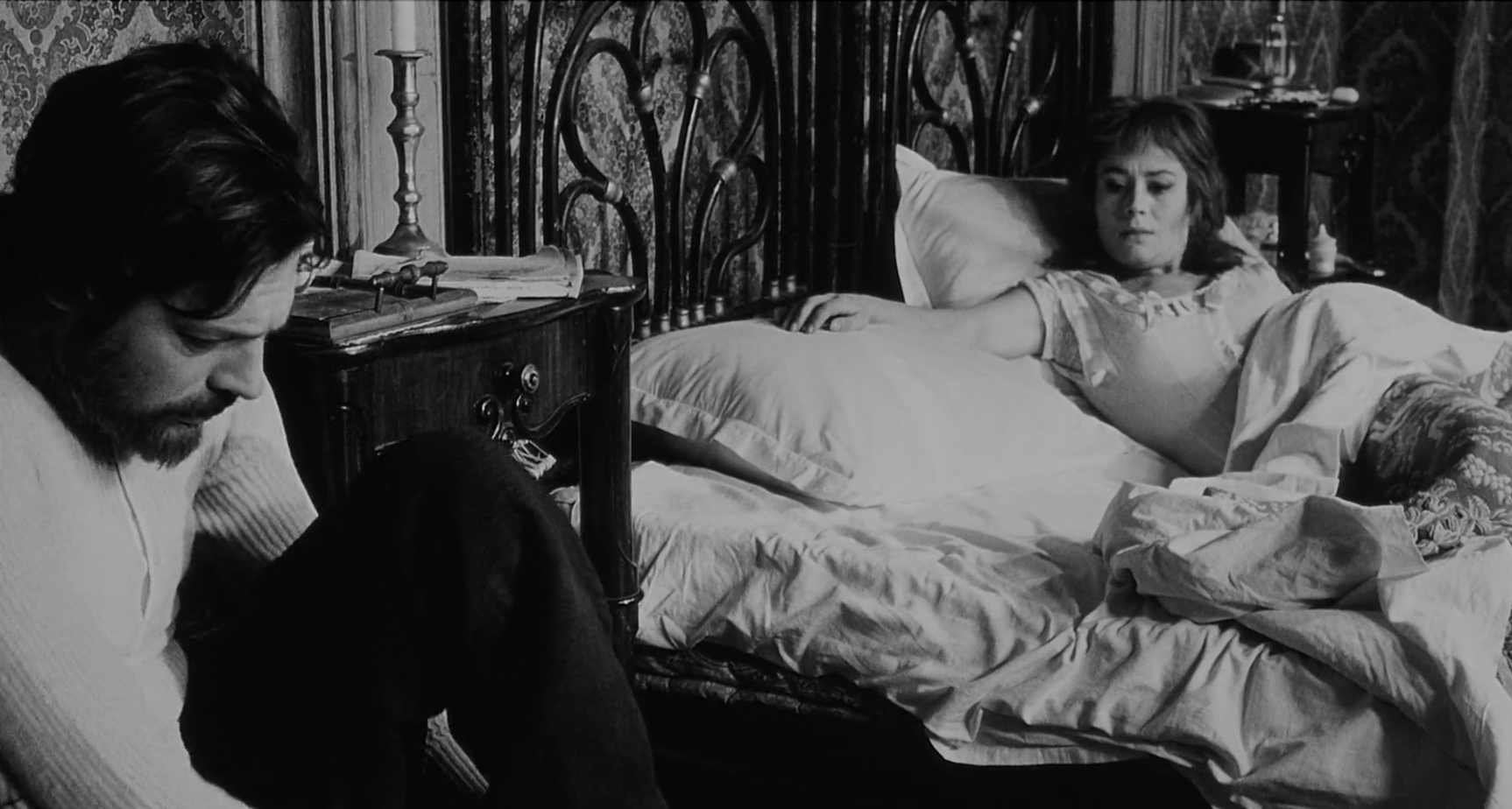

Mentre si sta vestendo, Niobe si sveglia: "Cosa succede?"

The Professor rushes back in. “Dammit!”

While he’s getting dressed, Niobe wakes: “What’s going on?”

Sembra preoccupata. “Cosa fai?”

"Devo uscire”.

"Ma ti arrestano!"

"Sì, è probabile. Anzi, è quasi certo”.

“E allora?”

“Devo andare!” dice ad alta voce. Poi più tranquillamente: “Devo andare".

She looks worried. “What are you doing?”

“I have to go out.”

“But they’ll arrest you!”

“Yes, it’s likely. In fact, almost certain.”

“So?”

“I have to go!” he says in a loud voice. Then more softly, “I have to go.”

"Te ne vai così?”

“Non ho tempo!”

“Senza dire niente?!"

Si mette il cappello. "Addio!"

"Non ci tornare più!" avverte lei, mentre lui esce.

“You’re going just like this?”

“I don’t have time!”

“Without saying anything?!”

He puts on his hat. “Goodbye!”

“Don’t ever come back again!” she warns, as he exits.

Al balcone, Niobe grida: "Finirai all’ospedale! Altro che in galera! Toh! Copriti almeno! Testone!" Getta la sciarpa dal balcone. Omero la raccoglie; il professore sta già pedalando via.

At the balcony, Niobe calls out, “You’ll end up at the hospital! Not in jail! Here! Cover yourself! Knucklehead!” She throws the scarf off the balcony. Omero picks it up; the Professor is already pedaling away.

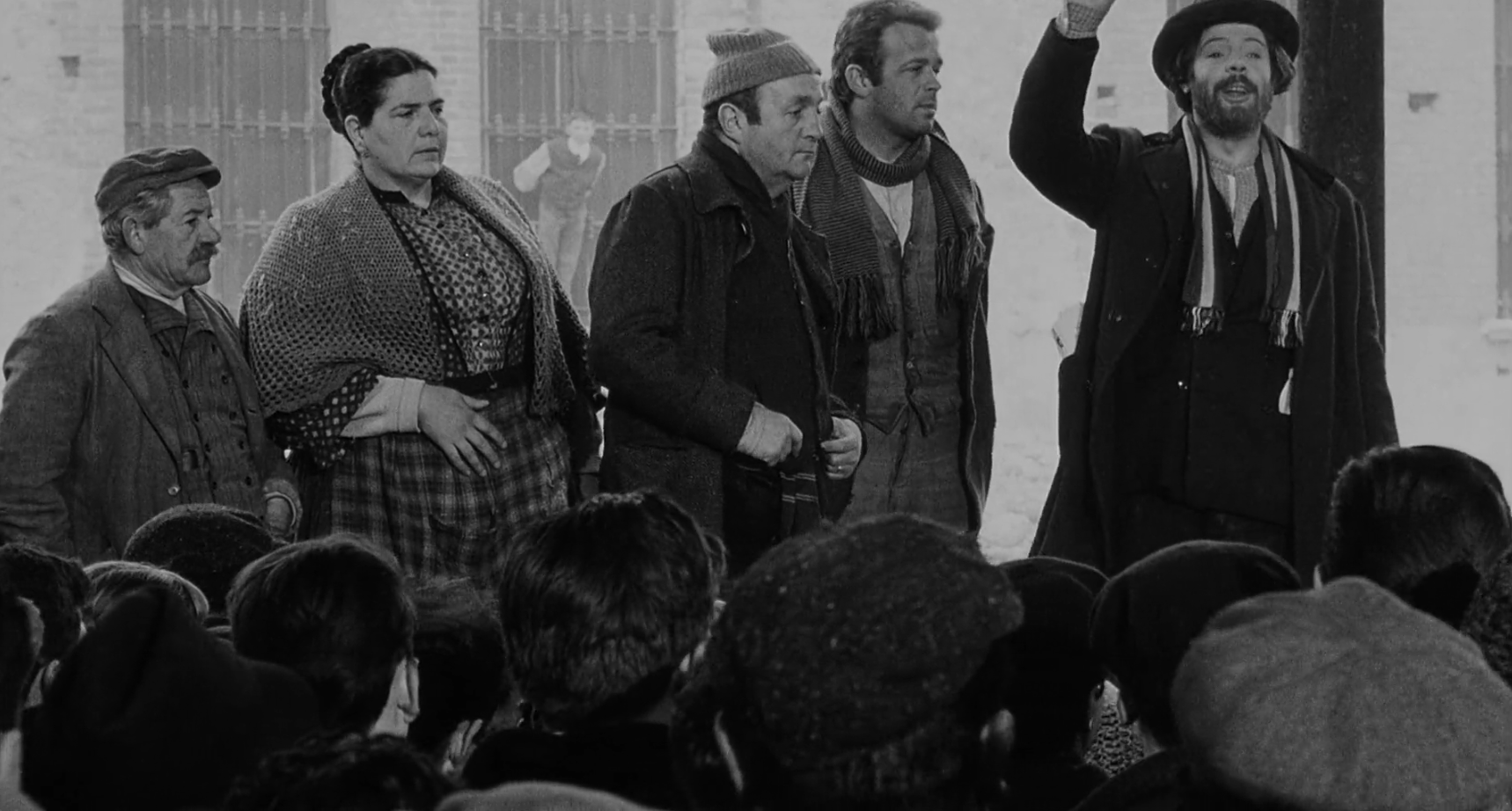

Al mercato all'aperto, vuoto, la macchina da presa fa una panoramica su una foresta di mani alzate. Davanti, il comitato – e Raoul – stanno in piedi su un palco.

At the empty outdoor market, the camera pans across a forest of upraised hands. At the front, the committee – and Raoul – stand on a raised platform.

Giulio dice: "Mi sembra che la maggior parte voglia ritornare in fabbrica".

Martinetti concorda.

"Non si sa" – obietta Raoul, prendendo tempo – "Prima contiamoli".

Giulio says, “It looks to me like the majority want to go back to work.”

Martinetti concurs.

“We don’t know that,” Raoul objects, stalling for time. “First, let’s count them.”

"Ma non li vedi?" risponde Giulio. Martinetti ha un'espressione stanca.

"Questa è una decisione importante" – insiste Raoul – "E voglio il conto dei voti uno per uno".

“But don’t you see them?” Giulio responds. Martinetti has a weary expression.

“This is an important decision,” insists Raoul. “And I want a vote count one by one.”

Allora Martinetti dice: "Va bene, va bene, facciamo la controprova". Si rivolge alla folla. "Chi è contrario a tornare in fabbrica e vuole continuare lo sciopero, alzi la mano".

So Martinetti says, “Okay, okay, we’ll do a verification.” He turns to the crowd. “Whoever is against returning to the factory and wants to continue the strike, raise your hand.”

Alcune mani sparse si alzano.

Si rivolge a Raoul. "Va bene adesso?"

Some scattered hands go up.

He turns to Raoul. “Okay now?”

"Contiamoli!" risponde Raoul, provocando un tumulto.

“Let’s count them!” Raoul responds, provoking an uproar.

Arriva il professore, pedalando furiosamente sulla bicicletta dello zio.

Here comes the Professor, furiously pedaling the uncle’s bike.

Si accosta alla parte posteriore del palco, dove Cesarina e Raoul si sporgono per aiutarlo a salire.

He pulls up to the back of the platform, where Cesarina and Raoul reach down to help him up.

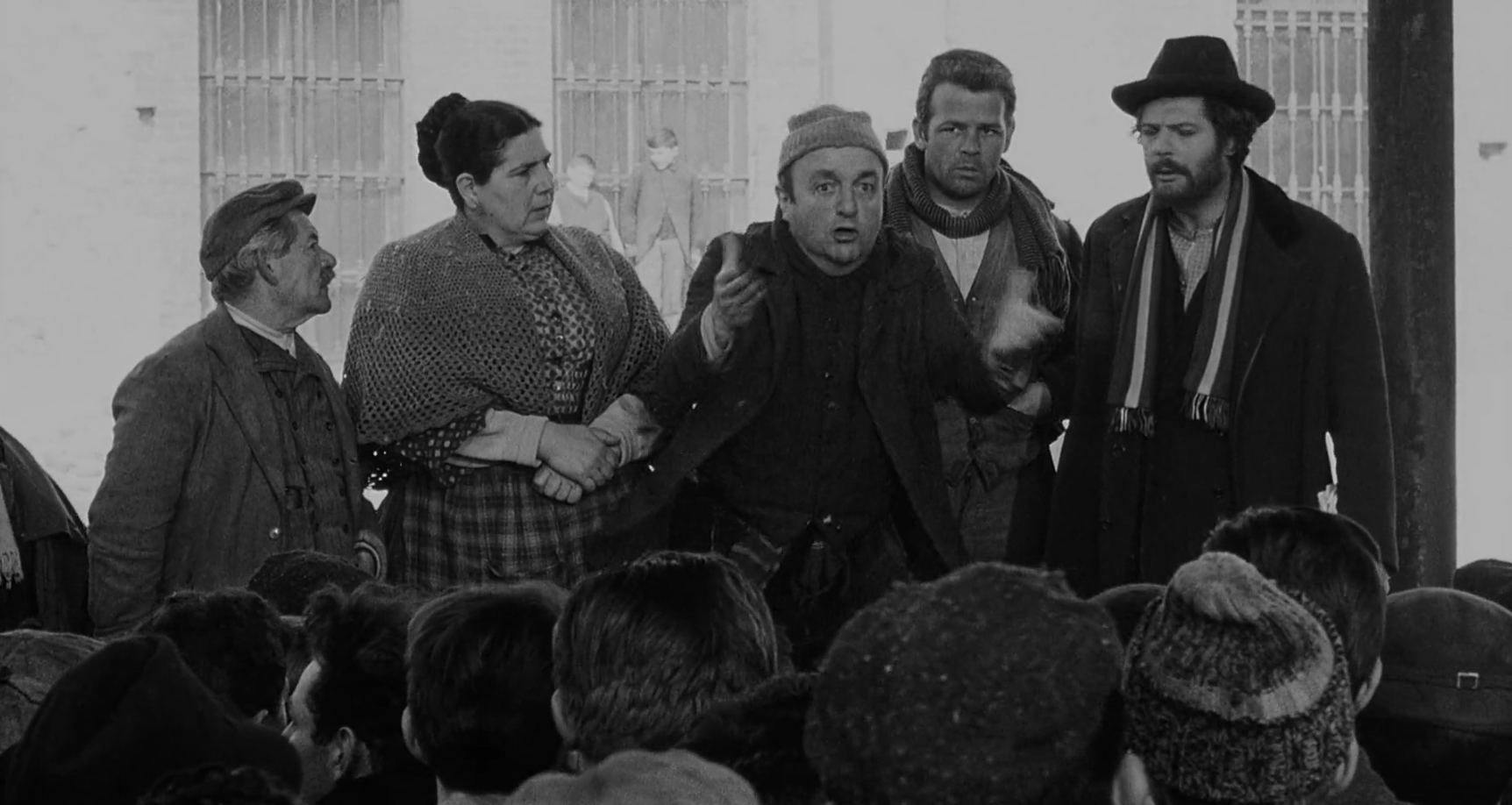

Il professore si trova senza fiato di fronte alla folla mormorante. "Scusate, scusate", balbetta, cercando i suoi occhiali. Raoul guarda il comitato con un misto di soddisfazione e malizia.

The Professor stands out of breath in front of the murmuring crowd. “Excuse me, excuse me,” he mutters, searching for his glasses. Raoul looks at the committee with a mixture of satisfaction and mischief.

Infine, il professore dice: "Nella fretta, ho persino dimenticato gli occhiali. Ma anche se non vi distinguo tutti, so lo stesso chi ha votato per la continuazione della lotta". Gli scioperanti restano in attento silenzio.

Finally, the Professor says, “In my rush, I even forgot my glasses. But even if I don’t single you all out, I know all the same who voted to keep up the fight.” The strikers stand in attentive silence.

"Barbero!"

"Sì, professore!" Barbero – lo studente della scuola serale che aveva scritto "Morte al Re" sulla lavagna – alza la mano. "Oggi e sempre!"

"Bene. Lo sapevo!"

“Barbero!”

“Yes, Professor!” Barbero – the night-school student who had written “Death to the King” on the board – raises his hand. “Today and forever!”

“Good. I knew it!”

"Gallesio!"

Gallesio, tra la folla, alza la mano. "Io non mi tiro indietro!"

“Bravo!”

“Gallesio!”

Gallesio, among the crowd, raises his hand. “I'm not backing down!”

“Great!”

"Bardella!... Come mai? Non è venuto Bardella?"

L'uomo alza a malincuore la mano. "Sono qua”.

“Bardella!... How come? Didn't Bardella come?”

The man halfheartedly raises his hand. “I’m here.”

Il professore annuisce. "Anche tu sei passato con gli altri..."

Una donna grida dalla folla: "Sono tutti dei cagasotto!" Si alza un applauso.

The Professor nods. “You’ve also gone with the others…”

A woman yells from the crowd, “They’re all chickenshit!” A cheer goes up.

Il professore li esorta a calmarsi. "No, non è vero. Non sono dei cagasotto. Sono la maggioranza. E la maggioranza è la voce della saggezza". Fa una pausa.

The Professor urges them to calm down. “No, it’s not true. They’re not chickenshit!. They’re the majority. And the majority is the voice of wisdom.” He pauses.

"Siete voi i pazzi! Tu, e tu Barbero, e tu!" Indica. "Voi che pretendete di lavorare solo tredici ore al giorno, voi che volete guadagnare pochi soldi in più, voi che vorreste evitare l'ospedale!"

“You’re the crazy ones! You, and you Barbero, and you!” He points. “You who expect to work only thirteen hours a day, you who want to earn a little extra money, you who’d like to avoid the hospital!”

"La maggioranza, invece è saggia. Sa che questo salario in fondo è sufficiente".

“The majority, on the other hand, is wise. They know that their salary is basically enough.”

"Tanto è vero che nessuno è ancora morto di fame. Sapete che secondo le statistiche, questo orario provoca incidenti solo al venti per cento dei lavoratori? Quanti siete qui? Cinquecento? Vuol dire che solo a un centinaio di voi toccherà di finire storpi".

“So much so that no one has died of starvation yet. Do you know that according to statistics, this work schedule only causes twenty percent of the workers to have accidents? How many of you are here? Five hundred? That means that only a hundred of you will end up crippled."

"Mondino! Dove sei?"

"Sono qui".

“Mondino! Where are you?”

“I’m here.”

"Fatti vedere!" L'uomo alza il braccio con una mano amputata. "È questo che vuole la maggioranza".

“Let them see you!” The man holds up his arm with an amputated hand. “That’s what the majority wants.”

Martinetti si rivolge a lui. "No! Sono trenta giorni che tiriamo la cinghia. Abbiamo perso! Non ha capito?"

"Chi lo dice?"

"Tutti!" esclama Martinetti, indicando la folla.

Martinetti turns to him. “No! We’ve tightened our belts for thirty days now. We’ve lost! Don’t you understand?”

“Who says so?”

“Everyone!” Martinetti exclaims, pointing to the crowd.

"Ragazzi, non è vero che abbiamo perso. È solo che siamo arrivati al momento più critico".

“Friends, it’s not true that we’ve lost. We’ve just arrived at the critical moment.”

"Vince la battaglia chi dura un'ora di più!" – grida, alzando la mano – "I padroni stanno peggio di noi".

"Chi gliel’ha detto?" lo sfida Martinetti.

“The one who holds out one hour longer wins the battle!” he cries, raising his hand. “The bosses are worse off than us.”

“Who told you that?” Martinetti challenges him.

"Lo so! Ho studiato queste cose, credetemi!"

"Non è più questione di credere!"

“I know! I’ve studied these things, believe me!”

“It’s not about believing anymore!”

Dalla folla vengono grida. "Le credenze* sono vuote!"

"Anche le pance!"

*Questo è un gioco di parole in italiano: “credenza” significa sia "fiducia ” che “dispensa”.

Cries come from the crowd. “Our cupboards* are empty!”

“Our stomachs, too!”

*This is a play on words in Italian: “credenza” means both “belief” and “cupboard.”

"Le pance saranno sempre più vuote e anche quelle dei vostri figli, se abbandonerete la battaglia! I padroni vinceranno sempre! E quella fabbrica, che vi dà solo miseria e fatica, darà loro maggiore ricchezza e potenza!"

“Your stomachs will always get more and more empty and your children’s too, if you give up the fight! The bosses will always win! And that factory, that only gives you misery and fatigue, will give them more wealth and power!”

"Ma la fabbrica mica è nostra!"

"Come non è vostra?!" I pugni del professore sono stretti dalla rabbia. "Chi ci lavora quattordici ore al giorno tutti i giorni per tutta la vita buttandoci sangue e sudore?”

Raoul lo osserva attentamente.

"But the factory is not ours!”

“How is it not yours?!” The Professor’s fists are clenched with anger. “Who works there fourteen hours a day every day all their lives, giving their blood and sweat?"

Raoul observes him carefully.

"Noi!" ruggisce la folla con una sola voce.

"Allora prendete la fabbrica, è vostra! Tornateci, sì, ma per occuparla! Dovete far capire a tutti che ci tenete più che alla vostra casa! Fate capire ai padroni, alla città e al governo che lì è la vostra vita e la vostra morte!" Si toglie il cappello con un gesto ampio.

“Us!” roars the crowd in one voice.

“Then take the factory, it's yours! Go back to it, yes, but to occupy it! You need to let everyone know that you care about it more than your home! Make the bosses, the city and the government understand that it’s your own life and death!” He takes off his hat in a sweeping gesture.

“Avanti! Andate, amici!”

“Forward! Go, friends!”

I lavoratori applaudono. Agitano le mani.

The workers cheer. They wave their hands.

Il professore li incita con il suo cappello malconcio e la grande folla, ancora acclamante, si spinge spalla a spalla verso la filanda.

The Professor urges them on with his battered hat and the great throng, still cheering, jostles shoulder to shoulder toward the mill.

FINE PARTE XI

Here’s the link for Parte XII of this cineracconto. Subscribe to receive a weekly email newsletter with links to all our new posts.